Blog posts for Technology and the Fate of Knowledge

- In Inference, Intuition, and Indian Philosophy

- The Epistemology of Kings

- The End of the Fate of Knowledge

- The Very Idea of Expertise

In Inference, Intuition, and Indian Philosophy

One of our goals in this module has been to broaden our awareness and understanding of different knowledge traditions with a view to recognizing the contingent, and historically-shaped, nature of the systems that are dominant in our society. These systems, once embedded, can seem self-evident and inescapable, not least because they structure, to a large extent, how we see the world. They appear to be incontrovertibly true. By looking at other, often incompatible, systems we can see that there are alternative, legitimate, equally rational ways of seeing the world.

Continuities

What was striking about Dr. Keating’s talk to me, however, was the continuity with European philosophical traditions. Dr. Keating structured his talk around a particular Gettier-like thought experiment:

Suppose you are walking through the wet market and you smell the unmistakable scent of durian wafting through the air. You might think to yourself, “ah, there’s durian over there!” even though you can’t see it. This isn’t a hunch or a lucky guess, but if it’s true there is durian over there, then you’ve managed to come to know something. Indian philosophers known as “Nyāya” or “reasoning” philosophers call this cognitive process “inference,” and they thought it was responsible not just for ordinary knowledge of things we can’t see, but also for harder cases, like the existence of the self or a god (whom they call Īśvara).

What is perhaps different from our discussion of Gettier cases in the seminars, is the extension of the thought to knowledge of a god but the rest seems notably familiar. Dr. Keating’s talk focused on the 17th century Nyāya philosopher, Annambhatta. Very little is known about Annambhatta but we do have his foundational work on logic and reasoning, in particular Tarka-Sangraha and Dr. Keating provided important insights into the context in which Annambhatta was writing.

This was the time of the Mogul Empire, an empire that, at its height, stretched across the Indian subcontinent from Afghanistan to Myanmar and from Kashmir, in the north, to the Deccan Plateau, in the south. The Indian economy was highly prosperous; indeed, it was the largest economy in the world by 1700. Dr. Keating described how Indian courts also frequently acquired, shared, and debated knowledge, philosophy, and science from Europe and likely a learned scholar like Annambhatta would have come across the works of René Descartes, David Hume, and other enlightenment philosophers. European philosophers were translated into Persian and I was struck by the continuities between Annambhatta’s systematic philosophy and that of his European contemporaries.

Annambhatta’s work covered an impressive range of subjects and concerns from rules of inference and reasoning, how to live the good life, the nature and existence (or non-existence) of the self, the nature of causes and effects, and the relationship between perception and knowledge. Dr. Keating didn’t explicitly say what Annambhatta would have made of Gettier cases but we have lots of examples from elsewhere in Indian philosophy that seem to aim at eliciting similar intuitions. The Indian philosopher Birnal Matilal collected these in his classic work on Indian epistemology, Perception: an Essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge. Look at how these compare with the cases we discussed in class and how they span a long history of scholarly work:

Suppose I close my palm and ask a gambler, ‘How many dice do I have in my palm?’ The gambler replies, ‘Five.’ And five it is. (12th century Indian philosopher, Sriharsa, in Matilal 1986, p. 136)

Suppose A has stolen something, and the police have got the suspect. Now two persons, B and C, come along to testify. B, who does not know, tells, simple out of malicious intent, that he has seen A in the act. And C, who has actually seen A in the act, says the same thing. The content of the belief of the police or the judge in both cases would be the same. But if the judge inflicts punishment on the basis of B‘s testimony rather than C‘s, we would feel that something has gone wrong. (A re-contextualisation of 6th century Indian philosopher, Candrakirti, in Matilal, p. 104)

Suppose somebody misperceives a cloud of dust as a line of smoke and consequently infers that there is a body of fire in the field beyond. Further suppose there is actually a body of fire there with or without smoke, but the person’s inference happens to be based upon a misperception. (Sriharsa in Matilal 1986, p. 136)

[S]uppose one (correctly) identifies an object at a distance as a cow by looking at a piece of cloth around the neck of the cow and mistaking it for the actual dewlap. (Sriharsa in Matilal 1986, p. 136)

On top of this, most languages seem to make a distinction between knowing and believing, the distinction that Gettier cases drive at. Given this, should we conclude that this intuition is a cultural universal?

Philosophers, one might argue, aim at universality. That is, they aim at a general claim. For example, a claim about knowledge and belief rather than a claim about knowledge in 8th century India or belief in 20th century United States. When philosophers write, ‘It seems that the person in this case, S, does not know,’ or ‘In such a case, we would surely say that S knows’ they do not mean by this that ‘I find it intuitive to say that S does not know’ or even that ‘We philosophers find itintuitive.’ That would be a rather uninteresting claim – who really cares what a particular philosopher feels is intuitive at any point in time? It is instead a shorthand for saying that competent, thoughtful speakers would, given the right conditions, find p intuitive (Cullen 2010, p. 4). By this reasoning, if you understand what the word ‘knows’ means you also understand that ‘knows’ is not identical to ‘believes’. If you don’t accept that, they imply, then you clearly don’t know what knows means.

I recently edited a special issue for the journal, Social Epistemology, which collects eight reviews of Yale-NUS professor, Bryan Van Norden’s, book Taking Back Philosophy. Van Norden has been arguing the case that philosophy departments should include more non-Western philosophy. This should be done because other philosophical traditions are different and come to different conclusions on substantive matters for good reasons. We should not assume, despite the superficial similarities observed in these Gettier-like cases, or in the fact that Annambhatta’s logic shares similarities with European works, that they are the same and we have nothing to learn from them. To see the differences, we must look more closely and that is not something that can be done in a short blog post but, shameless plug, interested readers might want to check out my upcoming chapter in the new Routledge Handbook on Social Epistemology out in June. To achieve this we have to go to the texts themselves: read closely and read deeply.

References

Cullen, S. 2010. “Survey-Driven Romanticism,” Review of Philosophy and Psychology 1(2): 275-296.

Kerr, Eric. 2019. “Epistemology without Borders: Epistemological Thought Experiments and Intuitions in Cross-Cultural Contexts,” in The Routledge Handbook of Social Epistemology, (Eds.) Peter Graham, Miranda Fricker, David Henderson, and Nikolaj Pedersen. Routledge.

Matilal, B. K. 1986. Perception: an essay on Classical Indian theories of knowledge. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

The Epistemology of Kings

Kings are not, as is sometimes assumed, an exceptional, unusual form of government. On the contrary, kingship is one of the most enduring forms of political governance (Graeber and Sahlins). We can’t know its precise historical origins, but it has been present throughout recorded history, and likely before! This means that if we want to understand the epistemic authority and its history comprehensively, we need to talk about kings. In this post, I consider whether we have kings today, not just in the literal sense that there are still monarchic nation states but also formally and functionally. In other words, are we still surrounded by figures who function as kings even while many countries have abandoned, or in some cases disposed of, their monarchs? I’ll argue affirmatively: we do see many of the tropes of kings in contemporary society.

Knowledge in medieval Europe

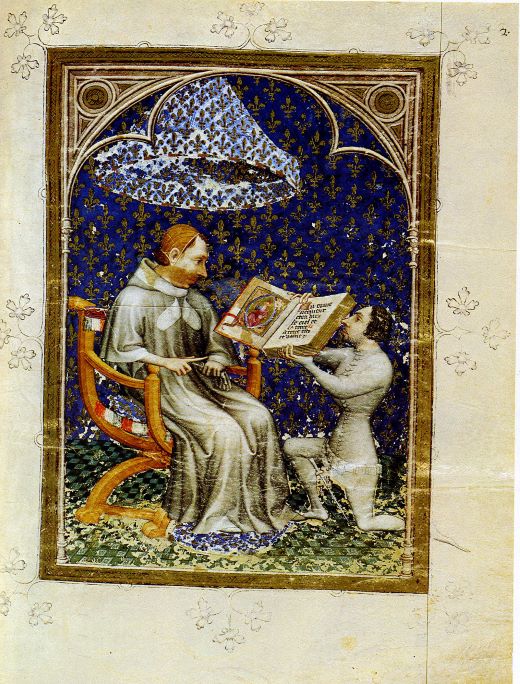

Kintzinger discusses how one particular king – Charles V of France – established and maintained epistemic authority chiefly through branding himself le roi sage or “the wise king”. Kintzinger sets his analysis against the background of knowledge in medieval Europe. He begins by noting that in order to understand medieval knowledge, we need to look at how it was part of, or was shaped by, medieval society. This includes ideas about order, religion, and scholarly and practical traditions and innovations. Interestingly, the imagination of epistemic authority is important in his portrayal of medieval knowledge. As a result, his analysis interprets artworks of the time, that portray popular imaginations of Charles the Wise as much as archival documents.

An abiding epistemological metaphor of the time was the “house of knowledge”. This came to prominence at a time when Aristotle’s texts were beginning to be rediscovered catalysing new research into natural processes and principles. Various proto-universities were being established around Europe (e.g. in Bologna, Paris, and Oxford) that laid the foundations for the modern university. These were not the first institutions that we can recognize as universities – early forms in Asia and Africa predate European efforts – and they differ substantially from the Humboldtian ideal of the early 19th century, but they are nonetheless notable for their influence since many of them survive until today. These early medieval European universities have their origins in Catholicism and, frequently, were founded by kings. Students were taught by monks and nuns and cathedrals and monasteries were beginning to introduce some of the first schedules using new time-keeping technologies and the conceptual innovation of discreet, measurable time in order to schedule regular prayer times and other monastic duties. In other words, they were creating an early form of the university timetable. As scholars at the time wrote: “Science has built itself a house.”

Kintzinger describes how the “wise man’s house” appeared throughout later centuries with different details but all containing one key element: the learned man among his books. He interprets one image of Charles V painted in his study with a copy of the Latin Bible open at the page which reads, “Happy is the man that findeth wisdom, and the man that getteth understanding.” Curiously, the manuscript continues in French a translation that replaces raison with prudence. The wise king was not merely a literary man (un homme de lettres) but one who had the sense of prudence required to put that wisdom into efficacious practice. The rejoinder to find wisdom and understanding serves to remind the king, and others, that knowledge is not freely at any person’s disposal. There is some knowledge that is “right” for the king and some that should be avoided or even banned.

Sovereignty now

Kings are not like us. There are no, and have never been, “man of the people” kings in the sense of the popularist politician. Throughout history the tendency has been for kings to become more common rather than less. Even when his subjects decide that kingliness is not for them, it has often turned out that kings are not very easy to get rid of and, even when one does manage it, a substitute tsar often pops up in his place. Graeber and Sahlins argue that, even in places were monarchies have been “once and for all” replaced, the legal and political framework of monarchy tends to live on. A notable example of this is the idea of “popular sovereignty.” The power once held by kings still exists but is shifted onto the people.

In fact, we can see a resurgence of kingly power in many forms of political life today. Perhaps the starkest of these is the corporation. Certainly, the likes of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk have the wealth of kings. The divine king ruled because, so the story goes, God put him there. God left the king in charge to manage, and impose order on, the population. Similarly, we might say that, in a modern corporation, the owner puts a manager in charge. The manager may well refer to his or her “people” in the same way that a king spoke of his “subjects”. Note that they are also required to present themselves as experts, as epistemic authorities, sometimes over a range of issues and domains in which they could not possibly be actual experts.

What is sovereignty today? Who or what does it reside in? The epistemology of kings suggests that it has been greatly shaped by the imagination of the king from earlier periods in history.

References

Graeber, David and Sahlins, Marshall. 2017. On Kings. University of Chicago Press.

Kintzinger, Martin. 2011. “Liberty and Limit: Controlling and Challenging Knowledge in Late Medieval Europe,” in Knowledge, Discipline and Power in the Middle Ages: Essays in Honour of David Luscombe, (Eds.) Joseph Canning, Edmund King, and Martial Staub. Leiden/Boston: Brill: 201-230.

The End of the Fate of Knowledge

Dear all,

This will be my final blog post for our Technology and the Fate of Knowledge Module – at least for this year! Now that all the workshops, all the Fellow’s Teas, all the seminars, all the field trips, are over, I’m writing in an effort to draw out some key ideas that I have personally taken away, from being a lecturer for this module but also that I have learned from each of you. This could be my own reflective workshop presentation (although a little longer than four minutes).

A central experience for me has been the exposure to radically different, possibly incompatible or incommensurable, ways of thinking about knowledge. Some of these came out of the texts we read: a wide range of disciplines from history to philosophy to anthropology to computer science. These were often challenging texts that brought their own epistemology – their own methods and means of determining the truth. Many of these texts wrestled with difficult questions that posed challenges to different disciplines and institutions (be it Hesiod’s challenge to poetry, Plato’s challenge to philosophy, Everett’s challenge to universal grammar, Kirk’s analysis of two possibly incompatible assumptions about animal knowledge, Minsky’s challenge to public opinion on artificial intelligence, Bostrom’s challenge to our everyday assumptions about reality or Frankenstein’s challenge to the conventional scientific community). Some incompatibilities came out of disagreements between ourselves and the text – the challenge of reading outside of our disciplinary preferences, not just of the struggle of something that can appear to be written in a foreign language even when it is not, but also struggling to understand the precepts behind a particular text: its purpose.

Behind all of this is the challenge of disagreement. What do we do when our beliefs conflict with another’s? It is not just that we might disagree over the facts – what is known – but we might also disagree over what counts as a means for arriving at the facts – the conditions under which something can be known; under which we can say, ‘This is true,’ or ‘This is false – fake news!’ It’s an experience that many of us have in our everyday lives but we may not recognize it in these terms and, through our discussions, I have acquired some new ways of talking about disagreement, with myself and with others. What should two experts do when they disagree? As we discussed in one of our seminars, what might two non-human artificial intelligences do? There are many answers. In seminars we looked at pluralistic, “polycentric” approaches, technological solutions, historical answers that lie in the changing nature of scientific knowledge. What seemed to become less plausible was the simplest answer: just defer to the expert.

Many experts visited us: scholars of Classical Antiquity, Indian philosophy, Chinese religion, feng shui experts, influencers and local celebrities. For me, a key moment here was the visit of Stephen Skinner. By all accounts, a scholar and practitioner of extremely varied capacities. An experienced feng shui consultant, extensive publisher of Western esoterica, and experts on the Graeco-Egyptian world who reads Ancient Greek. Certainly, an expert. Nonetheless, while interesting, compelling, and informative, I found his views challenging and difficult to fully defer to.

Before returning to these questions of disagreement and deference, I wish to briefly expostulate on an under-explored topic in our seminar discussions that is, nevertheless, crucially important to the fate of knowledge: the relationship between privacy and knowledge. We seem to be going through a change in our attitudes to privacy (and its possible antonym, transparency). Privacy, to my mind, is a tug-of-war between people who want to keep things private and people who want to gain access to those things. In other words, privacy becomes a live issue when someone wants to know something about you and you do not want someone to know that thing.

Take reading. For me, a very private moment is reading – I spend a lot of time doing it and I almost always do it alone. Some people like to read in public (on the train, at Starbucks), but the content of what they are reading is mostly private (unless you peer over their shoulder, which is generally frowned upon). Contrary to what you might assume, however, silent reading like this was not popular in Europe until around 1215CE, when the Church mandated confessions for the masses. It was the concept of private salvation that ushered in a new habit of silent learning and contemplation – in fact, early silent readers were sometimes thought to be wizards since, unlike everyone else, they read without moving their lips. Privacy is something that often invites suspicion. Socrates wrote: “For where men conceal their ways from one another in darkness rather than light, there no man will ever rightly gain either his due honour or office or the justice that is befitting.” Silent reading would become popular with ordinary people only around 500 years later when books were cheap enough for individual ownership. With social media and search engines recording the absent-mindedly written thoughts we have daily, are we moving back to a time when silent reading or personal reading habits are again transparent?

Privacy as a tug-of-war also involves a trade-off: a choice between money, convenience or prestige and the protection of your knowledge. But wherever privacy and wealth conflict, most people have chosen wealth. In 2015, when AT&T offered a $30 premium service that allowed users to opt-out of browser tracking for ad targeting, few users took it. Similarly, we could pay for services that do not, for example, analyse our emails, but most of us choose free providers. This has been true for some time. The landed gentry of Ancient Rome preferred homes with wide open gardens and courtyards that showed off their wealth and, when postcards were invented, many chose this cheaper method over one that secured their messages in an envelope. When telephones were introduced, individual telephone lines were prohibitively expensive; instead, neighbours shared one line, known as “party lines.”

So what is the fate of knowledge?

A pessimistic view might be that, like privacy, knowledge is dead (or at least dying). We will increasingly choose ever more invasive tracking in exchange for money, health advice, and entertainment. Every person see a different social media feed. When you think about it, it’s quite a bizarre situation. Worse, only the social media companies know what that feed is. Experts are no longer trusted, or have lost our trust, and with that the sense of communally-shared and agreed upon beliefs, and methods for arriving at those beliefs, dissipates.

A more optimistic view could be that new technologies open up new possibilities for challenging orthodox thought. Social media, whilst containing the potential for control, also has within it the seeds for the democratization of epistemic authority.

I don’t know exactly where I fall on this line between optimism and pessimism but it’s something I’ll continue to mull over as new technologies challenge our ways of thinking about knowledge. Thank you for all your contributions throughout the semester and I will hopefully see you around in the future!